In Conversation with Atina Sultani

Atina Sultani, a graduate of the Faculty of Fine Arts at Herat University, wields her drawing pens as a storyteller, capturing the painful and raw realities of Afghan women and girls through her vivid sketches. Since the Taliban’s return in 2021, her sketchbooks have become a lifeline of visual expression, echoing the silent struggles of thousands of Afghan women and girls forced into the shadows by suppression and censorship. In Afghanistan, artists create under a cloud of fear, and women, especially, have been silenced and stripped of their voices in every form—spoken, physical, artistic, and creative.

Now living in exile in Germany, Sultani has reclaimed her artistic freedom. Yet, her work remains an act of defiance, resistance, and unity, as Afghan women continue to endure the harsh grip of Taliban rule.

I spoke with Atina to learn more about her artistic practice and her life in exile.

Please could you share a little about your educational background and the work you did before you left Afghanistan? What were your career goals before the move?

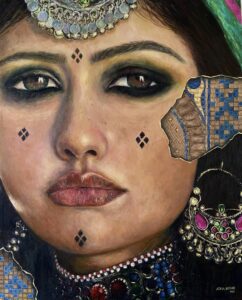

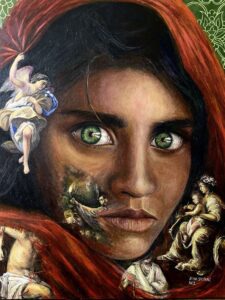

I studied painting for four years at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Herat University. During that time, I explored various styles and artistic worlds to find my own voice within the vast universe of art. Alongside this, I worked on illustration projects such as children’s books and magazine covers, and participated in several exhibitions. Eventually, my main focus became oil painting, and for my thesis, I created a large canvas exploring themes of plague and pandemic, blending classical European composition with Afghan symbolism.

At that time, I felt that art was beginning to gain real value in Afghan society, and my goal was to be part of this cultural awakening—to show that art can be a refuge, a weapon, a voice, and a way to preserve identity and history.

Unfortunately, just before my final semester began, the Taliban took control and universities were shut down. I tried to leave the country through Kabul but after the tragic bombing at the airport, I had to return to Herat. When the universities briefly reopened, I completed my final semester under great fear and pressure and managed to defend my thesis—though I had to leave the painting behind in the university archives, uncertain if it would survive.

How would you describe your artwork? We would love to start by knowing more about how you developed your unique style. Your illustrations are all in black ink with distinct sections standing out in red.

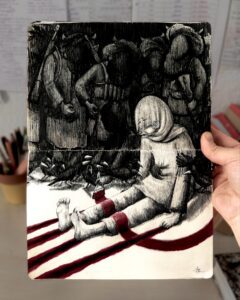

My illustration style was born on the first anniversary of Afghanistan’s fall, a time when unbearable grief weighed heavily on me, and I couldn’t express it in words. I turned to my sketchbook, and that moment marked the beginning of a visual language that was raw, urgent, and deeply personal.

At that time, I had just begun life as a refugee, carrying only a few pencils and a notebook. This sketchbook became a symbol of artistic survival in exile and an emotional document of displacement.

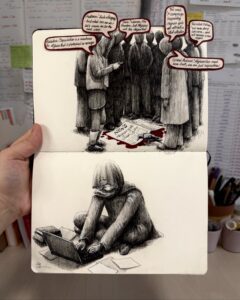

My drawings are primarily in black ink, with red used intentionally to highlight danger, violence, and psychological trauma. I often include crows, referencing ancient folklore where they symbolize bad omens or misfortune—reflecting the atmosphere many Afghans have lived through.

A recurring figure emerged in my sketches: a girl who symbolizes all Afghan girls whose identities, voices, and futures have been stolen. She carries my emotions but also represents collective silence, resistance, and memory.

Could you take us through your typical workday and the process of making your art? How do you come up with such detailed and imaginative ideas?

I’m not someone who easily talks about my pain or explains my feelings with words—that’s why I draw.

My ideas often come from the world around me: conversations with my mother, the pain my loved ones endure, the news, feelings of helplessness in the face of injustice, and the uncertainty of an unclear future. When words fail me, I express myself through drawing.

My workdays are quiet and internal. I carry my sketchbook everywhere, and sometimes ideas arise suddenly, sparked by a sentence, a memory, or a headline. I quickly sketch an idea, then refine it with black ink. Red highlights danger, trauma, or emotional tension. I often revisit pieces multiple times, layering in more meaning as I reflect.

At the same time, I carry the emotional weight of proving myself as an artist in exile. Migration has its own language—one in which you constantly have to say “I exist, I matter, I am here!” Otherwise, the silence of displacement swallows you.

How do you stay inspired and motivated to create given the current circumstances in your home country?

The current situation fuels my work. Exile, censorship, painful news, and distance from my family are heavy burdens I cannot carry inside, so I pour them out onto the pages of my sketchbook.

I draw so I don’t forget, and so we don’t forget. In Afghanistan, reading is not forbidden, but it is neglected. Because of this, history repeats itself over and over.

My art responds to this cycle. It is my way to preserve memory, resist silence, and tell stories that were never written or read.

For me, pain is not the absence of creativity but its spark. Creating helps me make sense of chaos and regain a small measure of control.

Talk to us a little about art as a form of protest and how it is effective in implementing change.

Where speaking out is dangerous, drawing can speak louder than words. It can cross borders, evade censorship, and reach places where politics fails.

My sketchbook is more than a collection of drawings—it is a visual archive of resistance. Every line carries sorrow, anger, and memory from moments when I felt invisible or powerless.

Many people have seen themselves in the silence of that faceless girl, and that’s when I realized the true power of protest art: it gives shape to feelings that many cannot express.

Art doesn’t shout, but it stays. It invites, challenges, and reminds. If it lingers long enough, it plants the seed of change.

Who are your inspirations in the art field?

I cannot name one specific artist as my main inspiration. My influences are scattered and come more from life itself than galleries or museums.

I am deeply moved by the emotional strength of everyday people, especially Afghan women who create beauty and meaning despite everything they’ve lost.

What advice do you have for Afghan girls still living in Afghanistan who want to develop their art and pursue the creative field in the current environment?

In a world where reactions are often performative, Afghan girls must become their own saviors—quiet heroes whose strength lies not in reaching a destination, but in standing tall despite everything.

Loving and creating art under such conditions requires immense courage and patience. Staying motivated is difficult—I have lived nearly two years under Taliban rule myself. Yet even in silence and fear, setting small goals gave me direction, and that direction gave me strength.

We may not win every battle, but what matters is that we show up, that we exist, and that we keep creating.

How can regular folks around the world support Afghan women artists and creatives?

In today’s virtual and real worlds, people are often drawn to shallow, flashy content rather than meaningful art.

Yet a single work of art can communicate as much as an entire book—sometimes even more. Art conveys details, truths, and memories that news headlines often cannot.

Supporting Afghan women artists is not just a favor—it is a sign of cultural maturity. It means choosing depth over distraction and substance over superficial noise.

At a time when many speak of “freedom of expression” but few uphold it, art remains a quiet but powerful form of resistance. Supporting it is one of the most meaningful ways to stand with the oppressed.

Interviewed by Shikha Sawhney Lamba

Atina Sultani (b. 2000, Herat, Afghanistan) is a visual artist whose work emerges from exile, memory, and resistance. Now based in Reinbek, Germany, she has developed a distinct visual language that merges classical oil painting, Persian miniature aesthetics, and contemporary narrative strategies to explore themes of womanhood, identity, and displacement.

After graduating with high distinction from Herat University’s Faculty of Fine Arts, she continued her artistic journey in migration. Through sketchbooks that function as visual diaries of exile, she has cultivated a personal voice rooted in fragility and defiance. Her drawings are not mere studies-they are visual archives of silence, trauma, and survival.

Her work has been exhibited at institutions such as the Linden Museum (Stuttgart), Neues Rathaus (Neumünster), and Wolfson College at the University of Oxford. She has collaborated with Integrity Watch Afghanistan and the French magazine La Déferlante, among others, and remains active in community-based visual storytelling particularly around migration, gender justice, and social resilience.

With her application to the Master’s program in Fine Arts, she aims to expand her interdisciplinary approach and deepen her critical visual practice. Her work speaks a language that is both political and personal-rooted in displacement, but moving toward reimagining and visibility.